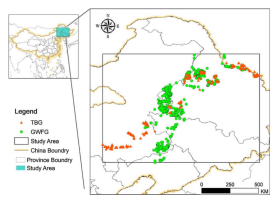

Animals respond to their environment at multiple spatial scales that each require different conservation measures. Waterbirds are key bio-indicators for globally threatened wetland ecosystems but their multi-scale habitat selection mechanisms have rarely been studied. Using satellite tracking data and Maximum entropy modeling, we studied habitat selection of two declining waterfowl species, the Greater White-fronted Goose (Anser Albifrons) and the Tundra Bean Goose (A. serrirostris), at three spatial scales: landscape (30, 40, 50 km), foraging (10, 15, 20 km) and roosting (1, 3, 5 km). We hypothesized that the landscape-scale habitat selection was mainly based on relatively coarse landscape metrics, while more detailed landscape features were taken into account for the foraging- and roosting- scale habitat selection. We found that both waterfowl species preferred areas with a larger percentage of wetland and waterbodies at the landscape scale, aggregated waterbodies surrounded by scattered croplands at the foraging scale, and well-connected wetlands and well-connected middle-sized waterbodies at the roosting scale. The main difference in habitat selection for the two species occurred at the landscape and foraging scale; factors at the roosting scale were similar. We suggest that conservation activities should focus on enhancing the aggregation and connectivity of waterbodies and wetlands, and developing less aggregated cropland in the surroundings. Our approach could guide waterbird conservation practices and wetland management by providing effective measures to improve habitat quality in the face of human-induced environmental change.